**Originally published on Feathered and Free which is being merged to MTTW.

Extinction is forever and there is no better reminder of that than the United States’ only once indigenous parrot species, the Carolina Parakeet. I wish I could give my usual bird profile with a map of where you can see them but sadly all I can do is direct you to the Charleston Museum. It’s a good reminder to support conservation projects before this happens to any other birds.

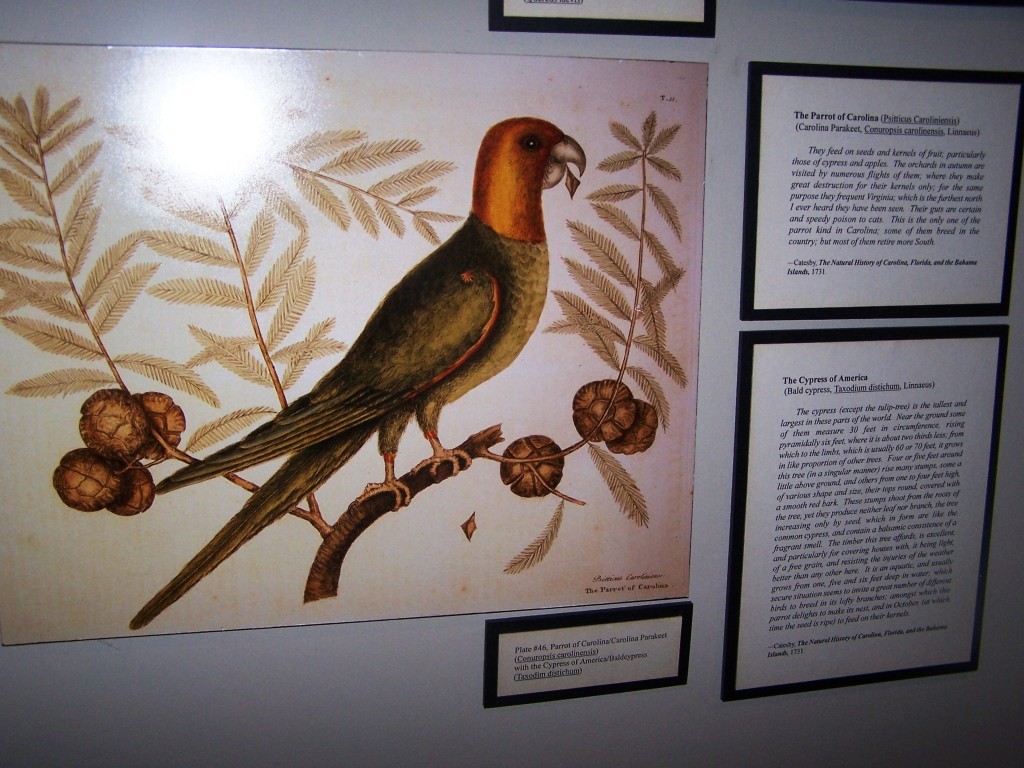

The Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) was the only parrot species native to the eastern United States. It was found from the Ohio Valley to the Gulf of Mexico, and lived in old forests along rivers. It was the only species at the time classified in the genus Conuropsis. It was called puzzi la nee (“head of yellow”) or pot pot chee by the Seminole and kelinky in Chikasha (Snyder & Russell, 2002).

The last wild specimen was killed in Okeechobee County in Florida in 1904, and the last captive bird died at the Cincinnati Zoo on February 21, 1918. This was the male specimen “Incas”, who died within a year of his mate “Lady Jane.” Ironically, Incas died in the same aviary cage as the last Passenger Pigeon, “Martha”, had done nearly four years prior. It was not until 1939, however, that it was determined that the Carolina parakeet had become extinct.

At some date between 1937 and 1955, three parakeets resembling this species were sighted and filmed in the Okefenokee Swamp Georgia. However, the American Ornithologists Union concluded after analyzing the film, that they had probably filmed feral parakeets. Additional reports of the bird were made in Okeechobee County in Florida until the late 1920s, but these are not supported by specimens.

The species may have appeared as a very rare vagrant in places as far north as Southern Ontario. A few bones, including a pygostyle found at the Calvert Site in Southern Ontario came from the Carolina Parakeet. The possibility remains open that this particular specimen was taken to Southern Ontario for ceremonial purposes (Godfrey 1986).

The Carolina Parakeet died out because of a number of different threats. To make space for more agricultural land, large areas of forest were cut down, taking away its habitat. The colorful feathers (green body, yellow head, and red around the bill) were in demand as decorations in ladies’ hats, and the birds were kept as pets. Even though the birds bred easily in captivity, little was done by owners to increase the population of tamed birds. Finally, they were killed in large numbers because farmers considered them a pest, although many farmers valued them for controlling invasive cockleburs. It has also been hypothesized that the introduced honeybee helped contribute to its extinction by taking a good number of the bird’s nesting sites.

A factor that contributed to their extinction was the unfortunate flocking behavior that led them to return immediately to a location where some of the birds had just been killed. This led to even more being shot by hunters as they gathered about the wounded and dead members of the flock.

This combination of factors extirpated the species from most of its range until the early years of the 20th century. However, the last populations were not much hunted for food or feathers, nor did the farmers in rural Florida consider them a pest as the benefit of the birds’ love of cockleburs clearly outweighed the minor damage they did to the small-scale garden plots. The final extinction of the species is somewhat of a mystery, but the most likely cause seems to be that the birds succumbed to poultry disease, as suggested by the rapid disappearance of the last, small, but apparently healthy and reproducing flocks of these highly social birds. If this is true, the very fact that the Carolina Parakeet was finally tolerated to roam in the vicinity of human settlements proved its undoing (Snyder & Russell, 2002).

The Louisiana subspecies of the Carolina Parakeet, C. c. ludovicianus, was slightly different in color to the parent species, being more bluish-green and generally of a somewhat subdued coloration, and went extinct in much the same way, but at a somewhat earlier date (early 1910s). The Appalachians separated these birds from the eastern C. c. carolinensis.

In November 2008, I visited the exhibit of the Carolina Parakeet in the Charleston museum. The taxidermied parrot specimen on display looked like a relative of the Jenday Conure. Like all conures, he would have had the playful, clownish personality. It is so sad that this species is gone forever and one more reason why we need to take care of the parrot species we still have, especially the endangered ones so we don’t lose them as well.

The taxidermied Carolina Parakeet